Deep Learning GPU Performance Analysis: Memory Bound vs Math Bound Operations

Determining whether a GPU operation is memory bound vs math bound is a crucial step in performance analysis because it informs the strategies to optimize the operation. Generally, a memory bound GPU operation is one where the overall computation time is dominated by memory access rather than the actual computation. Conversely a math bound operation is one in which the computation time is dominated by the actual computation rather than memory access.

Arithmetic Intensity and Ops/Bytes Ratio

Whether your GPU operation is bound by memory or by math depends on the following fundamental factors.

- How many math operations are required.

- How many memory accesses are required.

- The memory bandwidth of the particular device you are using.

- The math bandwidth of the particular device you are using.

There are other more obscure factors that come into play as well but these are the most fundamental. It is important to note that the first two factors are related to the actual implemenation of the GPU operation and the last two are related to the actual device on which you are performing it.

More concretely, the amount of time the operation spends accessing memory is equal to the number of bytes accessed divided by the device’s memory bandwidth i.e.

\[t_{mem} = \frac{\# bytes}{BW_{mem}}\]Similarly, the amount of time the operation spends on math is equal to the number of math operations required divided by the devices math bandwidth i.e.

\[t_{math} = \frac{\# ops}{BW_{math}}\]Consequently, the GPU operation is math bound if \(t_{math} > t_{mem}\) and memory bound if \(t_{mem} > t_{math}\). But it is often more convenient to use a bit of algebra to put the the device-level terms and operation-level terms on the same side such that a math bound operation would be one where

\[\frac{\# ops}{\# bytes} > \frac{BW_{math}}{BW_{mem}}\]and a memory bound operation would be one where

\[\frac{\# ops}{\# bytes} < \frac{BW_{math}}{BW_{mem}}\]The left-hand side of the inequality is called the operation’s arithmetic intensity and the right-hand side is called the ops/bytes ratio. So by calculating an operation’s arithmetic intensity and comparing it to the device’s ops/bytes ratio you can determine whether the operation is math-bound of memory-bound. It should also be noted that this comparison is only valid if the GPUs math and memory bandwidths are fully utilized, if not then the operation could instead be latency bound.

In terms of common deep learning operations, the following are typically memory bound due to the fact that they perform few operations per bytes accessed.

- Activation function computations (e.g. sigmoid, ReLU, etc.).

- Reduction operations (e.g. pooling layers in CNNs, batch normalization, SoftMax, etc.).

Math bound operations tend to involve large matrix multiplications. For example, a fully-connected layer could be math bound given that the input and weight matrices are large enough.

How do you Actually get the Numbers?

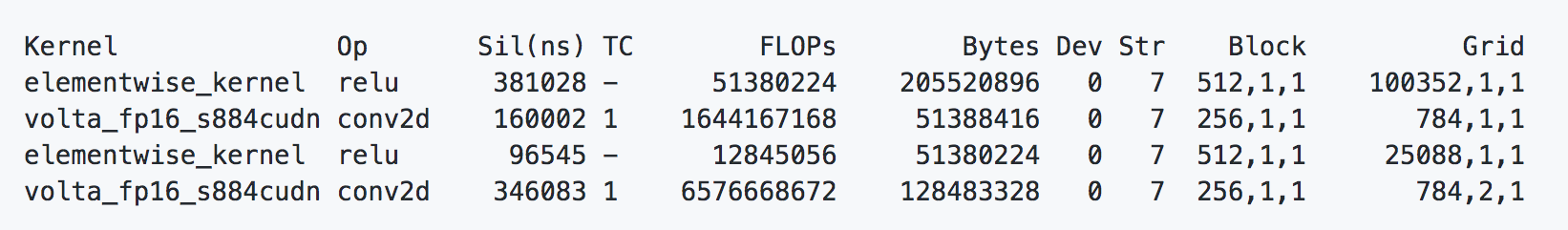

The memory and math bandwidth numbers are device dependent and can be looked up on the Nvidia GPU wiki page. As for the number of math operations and bytes accessed, this can be obtained from a profiling tool. A good choice for PyTorch profiling is PyProf. This tool can profile each kernel op in your PyTorch code and give you a report of all its relevant evaluation numbers in the following way.

Here the FLOPs column provides the number of math operations and the Bytes column provides the number of bytes accessed. Now you have all the information required to compute the arithmetic intensity, the ops/bytes ratio, \(t_{mem}\), and \(t_{math}\).

Additionally, PyProf provides the silicon time for each kernel op which is the total amount of time it takes to execute. You can compare the silicon time to the expected amount of time that the operation should take based on the GPU’s bandwidth i.e. \(\max(t_{mem}, t_{math})\). If the silicon time is significantly greater than the expected time then that might indicate that there is an opportunity for optimization (note however that this is only a first approximation).